When we look at a landscape, we do not see what is there, but largely what we think is there. We attribute qualities to a landscape which it does not intrinsically possess — savageness, for example, or bleakness — and we value it accordingly. We read landscapes, in other words, we interpret their forms in the light of our own experience and memory, and that of our shared cultural memory. (Macfarlane 2003: 18)

Rock climbers attribute qualities to a landscape, and claim ownership of their climbs by writing about their experiences. Climbing discourses mediate the exploration of the landscape and its written and pictorial representation. This paper examines how I as a climber know and experience landscape through the verbal and written word. As British academic Robert Macfarlane suggests, I began to learn to read and interpret the surface of the rock face before me through the shared cultural memory of a climber. Words render the formerly invisible nuances of a rock face, visible and real, and present the promise of an unexplored climbing route. The language of climbing associated with Mt Arapiles in Western Victoria informs both my studio practice and my engagement with a specific place. My art practice researches specific texts, guide books,1 climbing magazines,2 and club newsletters3 that reference the language, systems and structures through which the climbing fraternity constructs its vernacular landscape. These materials provide evidence that climbers share a common understanding and a particular reading of the landscape. Rock climbing publications affirm and reaffirm what climbers know and experience and will experience in the landscape. They demonstrate how language can create landscapes that suit a specific purpose and in turn influence our subjective experience of it. This sentiment is echoed by Australian academic George Seddon when he writes:

The way we use words tells us a good deal about the way we relate to landscape … The language of landscape, like all language, is loaded. The words we use both reveal and influence our perceptions of the environment, reflect our objectives and interests and affect our actions. (Seddon 1997: 24)

Does incorporating text in my art work of a specific linguistic and cultural context allow the experience of ‘reading’ the work to reflect the way the landscape is read and continues to be read by climbers?

There are a number of contemporary scholars who have explored the significance of place and the interrelationship between language, perception and place. Anthropologist Dr James Weiner invites us to accept that ‘the traces of people’s actions left on the earth and in the environment generally also leave traces in people’s consciousness’ (Weiner 2002: 270). This in turn affects our perception and participation in the landscape. Similarly, Macfarlane suggests when we attribute emotive qualities to the landscape we value it accordingly. This is particularly true when routes described in climbing guides as fun, engaging, intriguing and superb are highly sought after by climbers whereas routes described as ridiculous, bizarre and contrived are frequented far less. The existence of a language specific to climbing testifies to the long relationship, allegiance and intimacy that climbers and mountaineers have with the land. Archaeologists Meredith Wilson and Bruno David state that ‘People, places, and things are constantly engaged in a process of inscribing place. Through this process identities unfold in a continual process of (re)negotiation’ (Wilson and David 2002: 8). Climbers have inscribed the landscape of Mt Arapiles with their own personal stories, and the language they use has also evolved and adapted with each generation to describe the situations climbers encounter. There are currently over six hundred and fifty terms specific to rock climbing. To be claimed as a climbing landscape, Mt Arapiles had to be written into language and memory. Rock climbing guidebooks record a climbers’ conversion of space into place. According to humanist geographer Yi-Fu Tuan, ‘space is transformed into place as it acquires definition and meaning’ (Tuan 1979: 136).

Text as image is an integral part of my printed works. Fragments of writing are sourced and printed from my collections of interviews with climbers,4 unpublished handwritten notes and climbing guides. In investigating how other climbers experience the landscape of Mt Arapiles I was seeking a broader understanding of my own perception of Mt Arapiles. The selected texts are copied onto linoleum blocks, taking care to transcribe the sometimes subtle handwritten corrections that reflect individual styles and expressions of writing, and are then carved and printed using the substance of rock that climbers once touched. Working with the raw material of rock found on site at Mt Arapiles connects my intimate engagement with climbing to my art practice. Bodily capabilities are actively involved in creating our experience and understanding of the world around us. I physically crush rock and create surface textures to create an embodied experience and understanding of the landscape. Works that can be touched engage the viewer through handling, and provoke them to think about the way they use their senses to understand and position themselves in the world. Cultural historian Constance Classen suggests that when we distance ourselves from the contact with our environment we not only lose our tactile experience of its surfaces, but also other sensations that may be perceived. She writes, ‘Our environments, whether natural or built, tattoo our skin with tactile impressions … we learn how to value these impressions and how to use them to make sense of ourselves and the world’ (Classen 2005: 29).

In my concertina-style artist book Site Unseen II (2016), braille and text, printed as blind embossing on black paper, are hidden within the folded layers of the work. To read the content of the work, the viewer must dip their hand into a climbing chalk bag5 that rests alongside the book, and move their hands across the surface of the pages. It is only through repetitive touching with chalked hands that words become visible and sentences can be read. The words also become hidden through successive deposits of climbing chalk. It is the bodily movement of the reader, and not just a visual interaction with language, that this engagement requires. Just as chalk marks on the rock can guide a novice to the best available holds, traces of white chalk on the surface of the pages provide evidence of the reader’s passage. The imprint of the viewer’s hand memorialises a moment of contact, initiating a play of presence and absence.

Climbers engage with the landscape of Mt Arapiles and imbue it with meaning through physically climbing and writing about their experiences. The descriptions of climbing routes in Site Unseen II were transcribed from climbing guides and handwritten notes provided by climbers. By drawing on a variety of primary sources, my work addressed a particular historical framework and located climbing relationships as an integral part of artworks experienced by touch. The repeated marks and indentations on the paper were made by impressing rocks, from the site of Mt Arapiles, into the surface. The text and the marks suggests connection: the connections between climbers, between climbers and rock, between climbers and their world and between the viewer and touch. The rich black embossed paper provides a strong contrast to the soft white chalk. As the viewer touches the work, sentences emerge: ‘Daunting overhang, originally climbed without pre-inspection from abseil’, and ‘tenuous line with three bolts’. These descriptions reflect a language and terminology unique to climbing. They also reveal climbing events recalled by climbers who have modified the way they perceive and experience the environment.

This demonstrates how language can change our perception of landscape and, in turn, influence our subjective experience of it. This sentiment is echoed by Seddon when he writes, ‘Linguistic awareness is essential to self-awareness; if it is well developed we can modify the way we see the environment and act in and on it’ (Seddon 1997: 16). The process of touching and rubbing the surface of the paper with chalk provides a unique haptic engagement with the artwork. When Site Unseen II was exhibited in Melbourne in 2016 at MADA Gallery, Monash University and again in Brisbane at Webb Gallery, Queensland College of Arts during the Artist Book Brisbane Event (abbe), viewers engaged with the work in different ways. Some viewers sought to read the text before touching the work.

Some delicately touched the surface with their fingers, others ran their flat palm firmly against the surface. A common response after touching the work was to look at their hands to confirm the chalk residue imprinted on the skin.

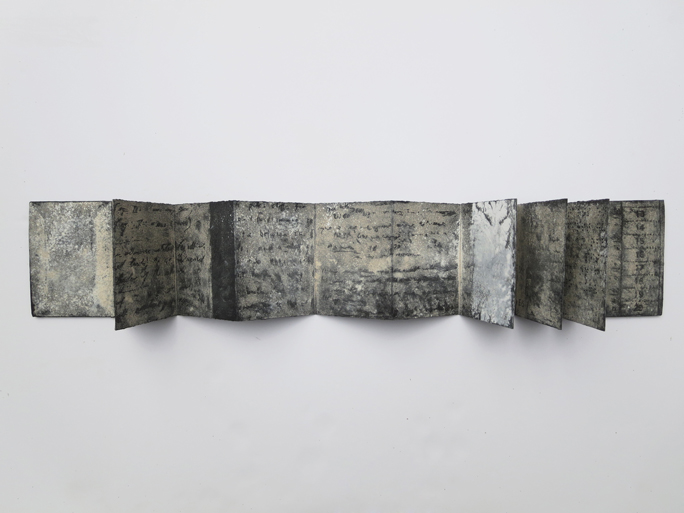

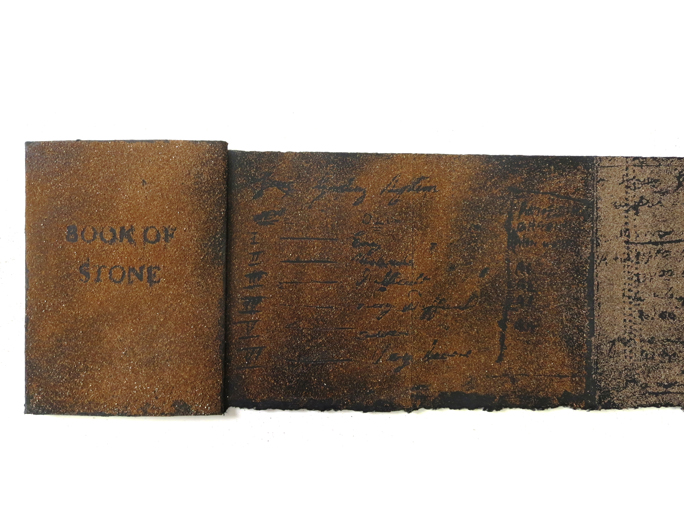

Artist books, in particular, offer a way to combine concepts of place and materiality that invite touch. Through the repetitive act of touching, books in general become worn, pages become creased and the evidence of the hand is revealed by marks and stains on the surface of the paper. The pages of my artist books, Book of Chalk (2014) and Book of Stone (2014) are printed with soft chalk, crushed limestone and quartzite (collected from the site of Mt Arapiles).

When repeatedly touched, the text is easily smudged and edges of the paper become worn. The chalk and rock imprints onto the viewer’s hand, which is then imprinted onto the surface again in a cycle of touch and being touched. The viewer’s touch of the work is a creative act. The viewer becomes the writer, with each touch the text is altered, readable passages become unreadable, another layer is added, suggesting a new reading. Just as the authors of climbing guides alter each subsequent guide via their corporeal and haptic knowledge of a climb, the viewer alters the legibility of the text through their haptic engagement with the book.

Although they are the same size, the two books feel different when touched. As the hand moves over the pages of Book of Stone the crushed limestone and quartzite has the propensity to be smoothed through constant touching yet feel granular on a textured and pitted surface. In contrast, Book of Chalk feels soft to the touch as the hand glides smoothly over each page. The pages of these artist books, like the face of a rock, carry a history of deterioration and wear on the surface. The substance of rock, which would have been worn away by time and weather had it remained at Mt Arapiles, is now touched and retouched in my artist book and eroded by the viewer’s hand. When closed, the books are the same size as the first Mt Arapiles climbing guides which were made to fit neatly in a back pocket.

The concertina format engages the viewer to look through the book either page after page, or as a long undulating series of folds, representing peaks, corners, and arêtes. The books evoke a number of related narratives regarding language and the haptics of place. The text references the collective memory of climbing routes at Mt Arapiles, and also creates a personal dialogue with the viewer through touch. Interactions with the work will vary, and the surface itself will change over time, discolour, and wear away; words will be revealed and concealed in an ongoing process of discovery. Similarly, the climber, revisiting a climb many years later, will find that familiar handholds have worn away, or the surface of the rock developed a black patina from the constant friction of climbing boots. Perhaps what becomes more evident in these works is the materiality of the surface. As the viewer’s touch removes evidence of the text, the remaining words become lost in translation, and run beneath the fingertips, half-felt half-remembered.

A climber experiences alternative ways of seeing and experiencing the landscape through touch; and similarly, alternative ways of experiencing a place are suggested to a viewer through my work Direct Start ★★ 5m Grade 8 (2016).

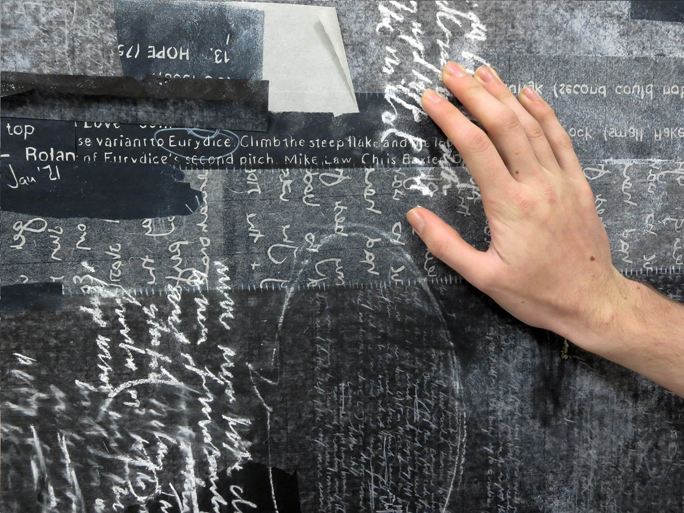

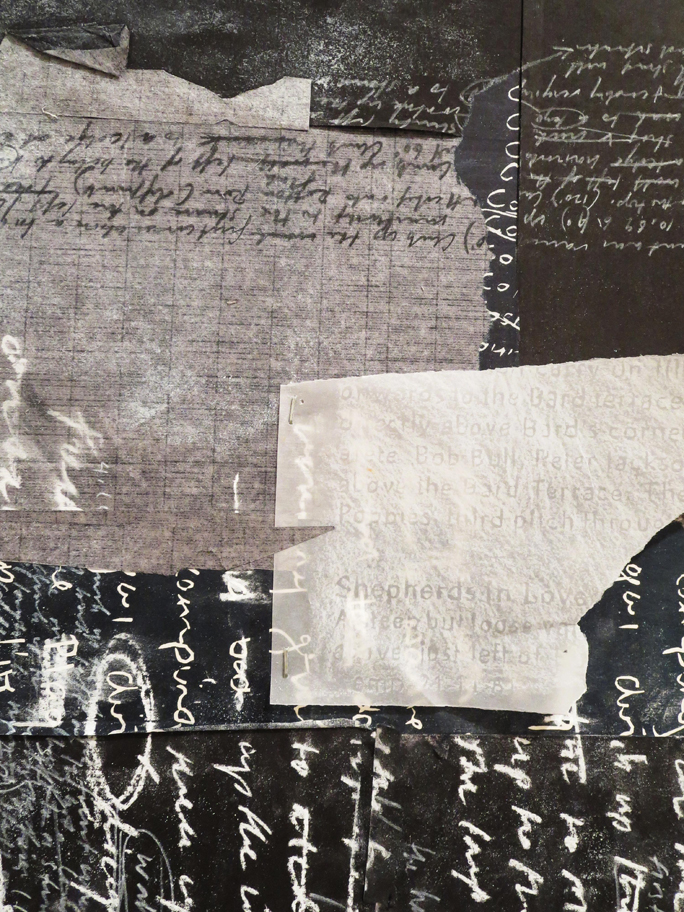

Variously-sized irregular-shaped panels are positioned at various heights, suggesting rock climbing features such as ledges and small platforms. I utilised my knowledge as a climber to calculate the position of each panel, assessing how one hold leads to another, and where one panel’s placement suggests the positioning of the next. Step by step the work, like the climb, is revealed. The title of the work references the practice of naming and grading climbs. The term ‘direct start’ used in climbing guides denotes that a climb can ascend from the ground up in a straight line, rather than traversing a wall from one side to the other to incorporate multiple features or holds. The title also includes a star rating (indicating the perceived quality of a climb), the length of the climb, and the grade. As the eye moves from the panels to the wall, the boundaries of distinctive pictorial space are challenged. Architectural features such as skirting boards, door frame and ceiling beams come into play with the work.

The bodily experience when viewing this work is like that of a climber surveying rock formations, ledges and platforms from the ground up. Viewers move from side to side, step back and move in towards the work, and look up and down to experience the work like a climb, from a variety of angles. Just as a climber looks for potential hand and foot holds and assesses the climb as a whole, each position provides a new reading of the shape and texture of individual panels and the work as a whole. Text in this work is used as a form of inscription — as various descriptions of climbs have been inscribed onto the landscape of Mt Arapiles, they are in turn inscribed onto the climber through touch. Similarly, the viewer inscribes my work through touch and in turn is inscribed by the chalk residue printed on the works.

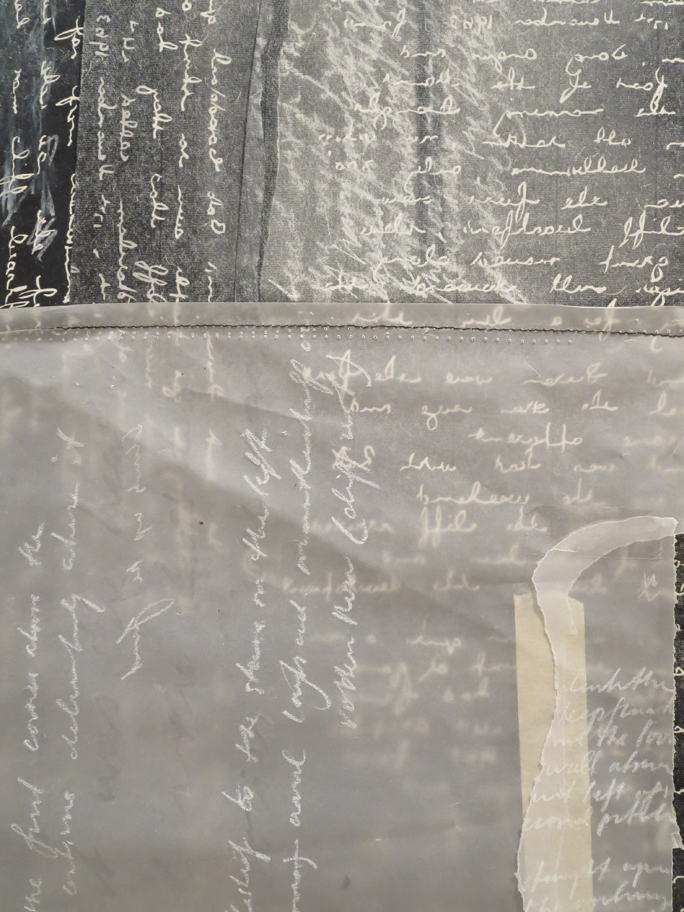

Panels layered and wrapped with printed text on paper, canvas, calico and organza reveal descriptions of climbs and handwritten notes. Different materials have different tactile qualities, and I use materials to trigger different memories and associations, and to offer contrast and resonances. Climbers camp in tents made from calico and canvas. The printed organza acts as a veil hiding and revealing layers of printed text. Transparent papers torn and taped together reference the changing visibility of climbs.

The texts were sourced from my conversations with climbers, their journals and climbing guides. By incorporating climbing discourse, I directly address my work to a particular historical and cultural framework. The text, sourced from my conversations with climbers, links my reading of the landscape and hence my perception of Mt Arapiles to my printmaking practice.

With repeated printing of linoleum blocks, some of the text was progressively obliterated and made illegible, just as published climbs become lost or unseen when then are overwritten by new routes. However, semi-legible fragments sometimes arise, as your eyes wander over the surface: ‘steeply up left past a bolt’, ‘climb the steep flake and … pull over the bulge’. These descriptions anchor the images within a field of narrative particular to Mt Arapiles. Climbing phrases simultaneously emerge from and recede into chalked surfaces that can be touched and retouched and alter with each subsequent viewing.

Much like the surface of the rock that changes over time with each passing climber’s bodily inscription, where holds become worn or chipped or coated with climbers chalk, a new reading of the wall is sometimes needed to complete the climb. Similarly, the viewer with each subsequent visit may find a new reading of the work. Not all the panels can be touched or easily read due to their positioning on the wall. The viewer can only touch what is within the reach of an outstretched hand. The legibility of the text and therefore the climb becomes clearer with close contact, just as a climber can read and utilise a hold more easily if they are close to the rock.

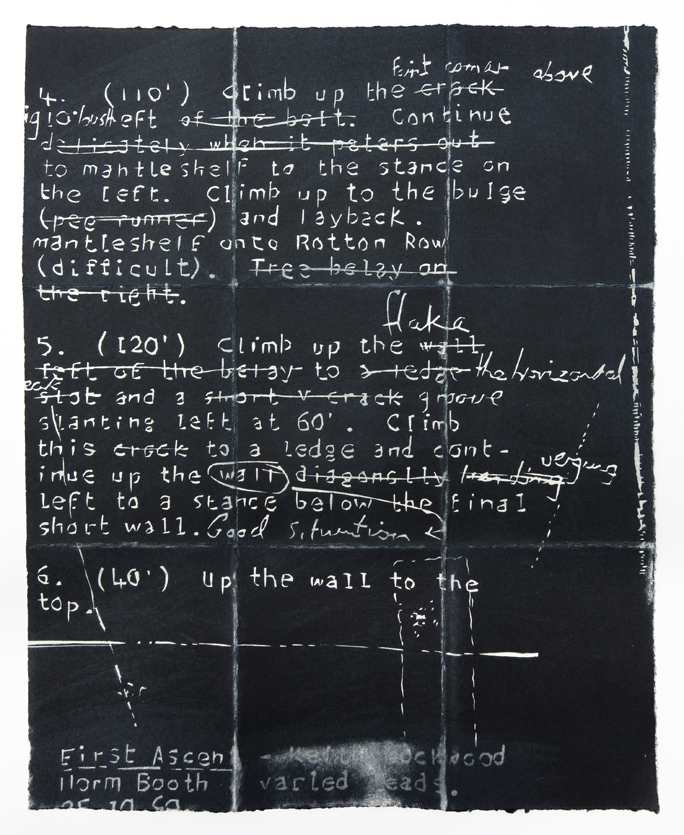

Of all the words used to describe climbing at Mt Arapiles, handwritten ones are the rarest. Presented as a set of seven loose pages, Site Revisited (2017) references a series of unpublished handwritten climbing routes by Australian pioneering climbers Chris Baxter, Keith Lockwood and Simon Mentz. I sought handwritten descriptions of climbs, as I am interested in the rhythmic action of writing and the traces left by the movement of the hand as it traverses the paper. By copying selected handwritten texts into my work, I replicate not only the meaning of the words but also the very act of writing. I trace the text onto linoleum blocks, carve out the text, and print the blocks numerous times. Through the act of reading, selecting, tracing, duplicating, carving and printing the original thoughts of the writer are sometimes rendered illegible in the final work. This suggests lack of clarity but can also suggest invisibility and lost histories. The paper, like the rock, becomes a site for a record of passage and erasure. In making my work, the corporeal action of writing, like climbing becomes an act of accumulation, repetition and ordering of knowledge.

Handwriting, rather than typed text, comes closest to expressing the immediate experience of engaging with rock. Typed text does not leave the same mark as its handwritten counterpart. When you draft a text on a computer screen, it can be changed, leaving no visible record of editing. Argentinian-born Canadian writer, Alberto Manguel, suggests: ‘Electronic space is frontierless … thanks to our word processors, there is no archive of our notes, hesitations, developments and drafts … we no longer record the evolution of our intellectual creations’ (Manguel 2008: 225–26). Selected climbing texts I have incorporated into my work show signs of corrections, and a going-over or a going-back to erase and reassess the written recollection. Arrows, inserts, and capitalisations are all used to reassert and clarify the original meaning. Words crossed out or corrected, thoughts scribbled in the margin, and later additions, provide a visual and tactile record of the changes. These additions are reminiscent of false starts in a climb where the path is not clear. The climber retreats and starts again, trying different holds, adding different parts, until the climb, like the work, opens up again with new possibilities. A rock face and a printed surface are sites where ideas are revised, stitched together, and reworked.

Perhaps what becomes more evident, particularly in my works Direct Start ★★ 5m Grade 8, is the rhythmic, bodily-engaged action of writing rather than the forming of legible words. Prints of handwritten text, like the chalk marks left on the rock by the climber, can add to, or can partly or wholly conceal what is already known, and alter perception in a continual and unpredictable process. Traces of chalk from your hands can guide a novice to the best available handholds. It can also mislead a climber into thinking that the chalked holds indicate the only way to complete a climb, when other alternatives are available. Similarly, written and oral descriptions of climbs can encourage or deter climbers from engaging with certain climbing routes. Using words to heighten or ‘gain vision’ in the landscape is discussed in detail in Robert Macfarlane’s book Landmarks. He states:

There are experiences of landscape that will always resist articulation, and of which words offer only a remote echo … but we are and always have been name-callers, christeners. Words are grained into our landscapes, and landscapes grained into our words. (2015: 10)

My creative practice has been enriched by my research of specific texts, such as guide books, letters and magazines which led me to reflect on the significance of language and its importance in mediating the pictorial representation of Mt Arapiles. In developing artworks that reflect a climber’s intimate temporal and sensory encounter with rock I present new possibilities for seeing and looking: where the viewer becomes an active agent in the reading of the work.

Notes

1 Australian rock climbing guides — Simon Mentz and Glenn Tempest (eds) 2008 Arapiles: Selected Climbs, Natimuk VIC: Open Spaces Publishing; and Kim Carrigan (ed) 1983 Mt Arapiles: A Rockclimbers’ Handbook, Melbourne: Impact Graphics — are designed to inform climbers where routes can be found, who climbed these routes and their grade of difficulty. They include maps, drawings or photographs of a given climbing area and written descriptions of individual routes interpreting the use of specific natural features on the rock.

2 Selected Australian climbing magazines Thrutch (1963—1979), Screamer (1977—1985), Rock (1978—2013) and Crux (2006—2013) were researched for their detailed published descriptions of climbing routes in Australia.

3 Argus is the official journal of the Victorian Climbing Club (VCC). It was first published in 1963 and was previously known as The Victorian Climbing Club Circular. It includes published information about climbing equipment, safety, access to new cliffs and updates of new climbing routes in Australia.

4 During the course of my practice-based PhD project titled Climbing the landscape: Mt Arapiles — explorations in place and the printed image (completed at Monash University in 2016), I documented conversations and recorded field surveys with over one hundred climbers camped at the base of Mt Arapiles. I drew on these primary responses in the course of my research to provide evidence that climbers share a common understanding of a paticular reading of the landsape of Mt Arapiles.

5 A fabric sack that holds chalk. It is usually attached to a belt around the climber’s waist. Chalk (magnesium carbonate) is used by climbers to absorb sweat for better grip.

Classen, Constance 2005 The Book of Touch, Oxford, UK: Berg

David, B and Wilson, M 2002 ‘Introduction’, in David and Wilson (eds), Inscribed Landscapes: Marking and Making Place, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1–9

Macfarlane, R 2003 Mountains of the Mind: A History of Fascination, London: Granta Books

Macfarlane, R 2015 Landmarks, London: Hamish Hamilton

Manguel, A 2008 The Library at Night, London: Yale University Press

Seddon, G 1997 Landprints: Reflections on Place and Landscape, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Tuan, Y 1979 Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press

Weiner, J 2002 ‘The Work of Inscription in Foi Poetry’, in Bruno David and Meredith Wilson (eds), Inscribed Landscapes: Marking and Making Place, Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 270–83