All cities are shaped by technologies of movement. We see this in the fabric of the metropolis, from the infrastructure of urban planning to the informal desire lines of pedestrian shortcuts. The forces of mobility that define a city are a reflection of its culture, history and commerce but they also generate constellations of sensory experience and ambience. Particular modes of mobility can lend a city a certain character. Where would Paris be without the Metro, Venice without its canals, or Amsterdam without its bike paths? In a sense, the way a city moves determines the kind of place it becomes.

We might wonder then if the city is always moving, in one way or another, can it ever really be known – can it ever be pinned down? In the 19th century the practice of flânerie was expounded both as a way of observing and describing the city and as a mode of comprehension in which movement about the urban environment could be a ‘vital intellectual activity’ (Ferguson 1997: 91). For the flâneur, the chosen mode of mobility was a kind of exploratory wandering, in which both the visual spectacle and hidden truths of the modern city could be gleaned in exquisite fragments. While a nostalgic mythology of flânerie continues to resonate through literary criticism and scholarship, other ways of inhabiting and knowing the city are more in line with contemporary living. There are other kinds of embodied perception and newer means of spectatorial cruising. It’s not that flânerie is dead, it’s just so last last century. Why walk when you can drive, after all?

Although the motorcar had taken hold of the boulevards of Europe by 1900 it would be wrong to suggest that the flâneur was a casualty on the road to automobility’s dominance. For like the city itself, the creative observer that saunters the streets is not a static entity. To keep pace with a changing metropolis and the spatio-temporal realities it demanded the flâneur had to adapt. The dandy had to learn to drive. And as the automobile multiplied in number, variety and velocity, writers, artists and architects were compelled to convey the thoughts and sensations it inspired. Central to the many realisations that came with driving is that the activity itself gives rise to novel ways of seeing and being seen. Thus with its blurs, gazes, and glimpses snatched through various framing devices, motoring has altered the way we visually read and relate to our environment.

For the most part people don’t really notice how they see when they drive. I suspect this is because even though driving generates a different approach to seeing, it is a process that has become virtually synonymous with 21st century existence. For generations now, from the cradle to the grave (the hospital-bound car and the hearse) we humans have been raised in a cocoon that rolls on rubber and consumes the fossils of the earth. At present a billion cars are travelling the roads of the planet (Sousanis 2011) and a new car is birthed every half a second (Worldometer 2014). Moreover, we have freighted the car with an immense symbolism relating to liberty, democracy and citizenship. So perhaps it is no surprise that we have absorbed the view from the backseat and through the windscreen as an ordinary and routine part of life. Although the signature of the automobile is all around us, through its very familiarity it often goes unnoticed. It is this effect of the everyday—the power to hide in the light—that I find intriguing and it has influenced my approach to car culture as an artist.

The Car Yard series emerged out of an attentiveness to the embodied experiences of driving and a desire to reflect on the blinding ubiquity of automobility. I wanted to find a new way to picture the car and at the same time acknowledge driving as a seeing and thinking activity. The more I became aware of what I experience when I drive, the more I noticed what catches the eye. There are sights that are hard to ignore: signals and flashing lights, for example. There are also billboards, and neon signage, ‘gigantic’ sculptures, as well as restaurants and various drive-in facilities that are uniquely designed for an automobilised public. I grew aware of the various ways the city is constructed to attract the senses of the driver. Like the glass reflector beads that make up glowing turn arrows by night, the tactics and materials deployed are based on an aesthetics of movement, shimmer and shine. Often placed along the roadside, these devices range from balloons bobbing in the sky, flags, glittering ‘flicker beads’, to moving inflatables and ‘cat’s eyes’. There was one particular site where I found many of these optical devices coincided: the automobile sales yard.

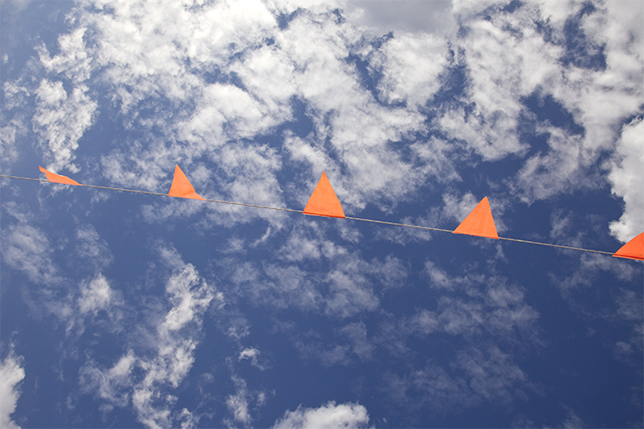

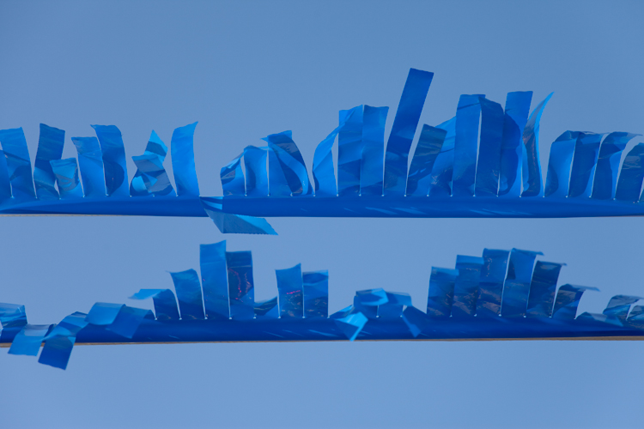

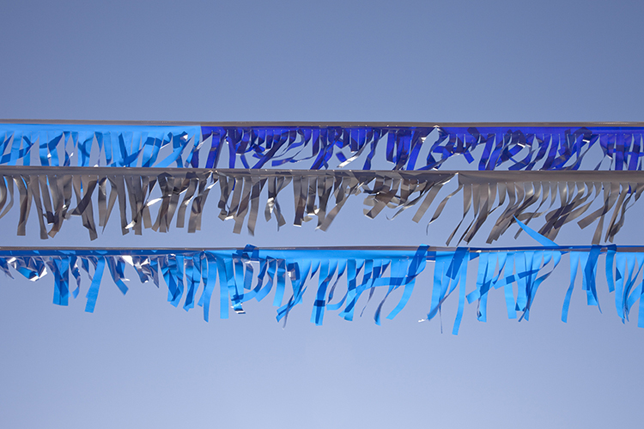

The car yard is a central site in the mythic landscape of automobility. It is a place where fantasies are sold and dreams are purchased. The bunting that frames the car yard plays a role in sustaining this image. Its bright colours and sunlight-reflecting plastic is inherently optimistic. Even its position flittering against the sky is somehow aspirational. That is, until the sparkle wears off and the UV resistant plastic can resist no more. Once the wind and the sun and the forces of the weather take their toll, the strands of promise become undone.

To my eye both the brand new shiny strands and the torn and tawdry remnants are a powerful and poetic allegory of automobility’s inherent paradox. They are both prayer flags and tattered hopes, desires and disappointments.

Bunting is most commonly found in two types: the Hawaiian skirt (or ‘fingered’) variety and the pennant, triangular kind. Yet through a combination of factors, including colour, condition, number of strands and shape every car yard’s bunting is slightly different. My photographs amplify this variation, and draw a connection to a climate in flux, by recording the bunting against different skies and light. By abstracting automobility in this manner, I aim to reflect on the contradictory ideas and emotions that underlie our relationship with the motor vehicle. Nevertheless, each photograph effectively stands in for a different car yard somewhere in Australia, Japan or America. As a collective they represent the car’s global expanse and to capture their uniformity and their uniqueness I had to travel about on wheels. Hence the Car Yard series was dependent on my own mobility —born of my practice as an artist-driver cruising the twenty-first century city.

Ferguson, Priscilla Parkhurst 1997 Paris As Revolution: Writing the Nineteenth-Century City, Berkeley, Los Angeles, Oxford: University of California Press.

Sousanis, John 2011 ‘World Vehicle Population Tops 1 Billion Units’ WardsAuto at http://wardsauto.com/ar/world_vehicle_population_110815 (accessed October 20, 2014)

Worldometers, ‘Cars Produced this year’ at http://www.worldometers.info/cars (accessed Sept 28, 2014)