The Visions of Australia program, established in 1994, plays a significant role in the touring of exhibitions from, and to, regional and interstate locations across Australia. Through an examination of Round 32 of the Visions of Australia program this article explores the intersection of localities in the conception of a national culture. Focusing on the exhibitions MAYS, Australian Minescapes, Smalltown and Robert Dowling it illustrates that assemblage theory presents an alternative conception of national culture that focuses upon relationships and networks, as opposed to a traditional conception of a set society and culture. Within the framework of Latour’s ‘society of assemblages’ it concludes that these exhibitions operate within a heterogeneous national culture that is continually redefined and reoriented through a spectrum of external and internal relationships.

Keywords: assemblage – exhibitions – cultural studies – museums – art – nation

In March 2010 the exhibition Australian Minescapes was opened in two rooms of the Gold Museum at Sovereign Hill, Geelong. Sovereign Hill is Australia’s largest outdoor museum, which recreates the mid-nineteenth century gold mining town of Geelong and explores gold mining’s impact on the state of Victoria, and Australia more broadly. Australian Minescapes consisted of 28 images, taken by Canadian photographer, Edward Burtynsky, of mines and mining sites in Western Australia. These photographs, produced as large 2 x 2 metre prints, illustrate in lurid detail the open cut mining operations in the eastern parts of Western Australia. Discussing this exhibition on ABC Radio Ballarat the Deputy Director of the Museum, Tim Sullivan, said:

Everyone will appreciate seeing parts of Australia many people will never get to see. To see them in this scale, and to the level of detail and colour, it is just extraordinary. (ABC 2010)

Australian Minescapes toured to Sovereign Hill through funding provided under Round 32 of the Visions of Australia (VoA) program. Under this program the exhibition toured to another four sites, across four states in Australia, engaging and impacting upon diverse audiences with locality specific subject matter. Within this space Australian Minescapes operates within, and across, a complex national culture, that is continually redefined by its component parts. Within Round 32, the VoA program provided development or touring funding to 14 exhibitions that would tour across more than 59 sites in Australia. Each exhibition brought a distinct aspect of Australian society, aspects which were often tightly connected to a specific locality, to a diverse audience within both metropolitan and regional communities. They created sites in which a national conversation could be had about our cultural identity; a conversation that did not simply acknowledge the cultural development of our communities, but redefined our conception of society and culture. This article will examine four exhibitions toured under VoA Round 32 through the framework of assemblage theory. It will explore how these exhibitions interconnect to create points at which cultural assemblage components remove and reconnect, interacting across small, defined assemblages and a larger, complex assemblage (or network of sites) defined here as a national culture.

At its core, assemblage theory posits that society is defined by relationships of exteriority, rather than concepts of interiority. Consequently, society itself consists of numerous assemblages, which are each defined not only by the ‘result of an aggregation of the components' own properties but of the actual exercise of their capacity’ (DeLanda 2006: 11). More plainly, it is not simply the make-up of these assemblages that defines them, but the internal and external relationships and interactions that they take part in. This departs from a conventional pedagogical position of social analysis in which social actions and circumstances can only be analysed within the context of a set (or slowly evolving) underlying social structure (Bennett & Healy 2013: 1). Assemblages are not only defined by their own internal associations and relationships, but also have their own relationships of exteriority, with the capacity for assemblages and their component parts to form new, larger assemblages within the social structure. This reorientation means that rather than investigating the consequences of a range of social components upon a homogenous society, assemblage theory requires the identification of stabilised assemblages and the analysis of their internal and external engagement, segregation and interaction within an inherently heterogeneous society. This framework naturally facilitates recent trans-disciplinary and transnational research methodologies that work across cultural and historical studies; most recently illustrated in Australia by the Australia Council Research funded project, Museum, Field, Metropolis, Colony: Practices of Social Governance project at the Institute for Culture and Society led by the University of Western Sydney. It has also facilitated analysis of concise and well defined social constructs, such as roadside memorials, public art pieces, and museums (Campbell; Hillias; Waterton & Dittmar).

Foundational works have already begun the analysis of regionally and nationally defined assemblages. Manuel DeLanda focuses upon geographic and organisational frameworks dominated by an examination of land succession that is further complicated by the interactions of populations and regions to a central locale. He defines this within the physical relationships that are inherent in sub/urban sprawls. In his long term analysis of the formation of nation states, focused upon the late-medieval period in Europe, he concludes that:

every social entity is shown to emerge from the interactions among entities operating at a smaller scale. The fact that the emergent wholes react back on their components to constrain them and enable them does not result in a seamless totality. Each level of scale retains a relative autonomy. (DeLanda 2006: 118-119)

Alternatively, Bruno Latour stresses the need to decrease/remove the conceptions of the macro and micro, the centre and periphery, to facilitate the examination of a ‘society of assemblages’. Here he posits that when society is conceptualised as a network:

Macro no longer describes a wider or larger site in which the micro would be embedded... but another equally local, equally micro place, which is connected to many others through some medium transporting specific types of traces. No place can be said to be bigger than any other place, but some can be said to benefit from far safer connections with many more places than others. (Latour 2005: 176)

Examined through Latour’s ‘society of assemblages’, the objects, artworks and narratives contained within VoA touring exhibitions operate in heterogeneous spaces, where nation, region and locality intersect in the telling of an ‘Australian’ story. Within a post-Howard realm, where a plural, diverse and multicultural Australia has become progressively contested by a homogenous, Anglo-Celtic conception of history and culture, these two separate paradigms for approaching a national culture need to be re-examined (Witcomb 2009: 49). Assemblage theory, with its pedagogic turn that facilitates the examination of both methods of conceptualising culture, provides the structure on top of which this analysis can take place. The VoA program is an appropriate subject for this study, due not only to the multiple content presented through the touring exhibitions, but also the diverse and disparate audiences to which this content is presented. The VoA program was established in 1994 to support the development and touring of exhibitions, from local, state and national organisations, to regional and city locations and venues in at least three different states or territories across Australia. Throughout most of its history it operated under the former Department of Communication Information Technology and the Arts, before moving to the Ministry for the Arts. For a period of three years coordination of the program was passed to the Australian Council for the Arts, before returning to the Ministry in 2015/16.

Throughout its lifetime VoA has been used by National Collecting Institutions (NCIs) to support the touring of significant collections to a variety of State Collecting Institutions and regional museums and galleries. These NCIs include the National Museum of Australia, Australian National Maritime Museum, Australian War Memorial, National Gallery of Australia and National Library of Australia.[i] It has also been used by state and local museums and galleries to develop and tour both art and cultural heritage exhibitions to regional and metropolitan locations. Funds are granted for the costs associated with development of touring exhibitions and/or the costs of touring these exhibitions. Organisations are encouraged to obtain seed funds to develop an exhibition, before seeking a second grant to support the touring of the same exhibition. This was crucial throughout periods where the capacity of NCIs to tour their collections to sites outside of Canberra were affected by limitations and cuts placed on their budgets. Each NCI is constituted under its own Act of Parliament, and consequently operates independently, with set yearly budgets. Recently these relatively modest budgets have been significantly impacted through the implementation of an increased efficiency dividend by successive Australian Governments throughout the 2000s (Barneveld 2009). VoA is not a unique program, with similar funding available through the Renaissance Strategic Grants program, overseen by the Art Council of England, the Swedish Exhibition Agency touring program, and the Smithsonian Institution Travelling Exhibition Service in the United States of America. The International Council of Museums also hosts the Committee on Exhibition Exchange to encourage the touring of exhibitions between countries. However, the VoA program is the first Government coordinated initiative to tour exhibitions within Australia, and continues to offer significant opportunities for audiences in regional and interstate locations to access significant cultural collections.

Exhibitions toured under Round 32 of the VoA program represent a diverse range of exhibition types and touring exhibitors, that are absent from subsequent funding rounds. The same year of this funding round, 2009, was also the year that the National Collecting Institutions Touring and Outreach (NCITO) program was introduced. The NCITO program provides funding to NCIs to facilitate the touring of exhibitions within Australia and internationally. Prominent exhibitions featured in this scheme include Papunya Paintings that was developed by the National Museum of Australia and toured to the National Art Museum of China, and Australian Portraits: 1880 to 1960, toured by the National Gallery of Australia to locations in Queensland and the Northern Territory. It responded to real impacts upon the touring exhibition schedules of these institutions as a result of the efficiency dividend. For example, the National Gallery of Australia was forced to reduce their number of touring exhibitions from 14 in 2007/8 to 9 in 2008/9, with only one new exhibition developed in this final year (Barneveld 2009: 13-14). Prior to the introduction of NCITO, NCIs submitted applications for support under VoA. This, coupled with the grant administration moving from the Ministry of the Arts to the Australia Council for the Arts in 2012, has seen a reduction in the number of cultural heritage exhibitions toured by VoA, in comparison to visual arts exhibitions. As such, VoA Round 32 represents a combination of exhibition touring institutions (both regional and NCIs) and a high diversity of cultural heritage and visual arts exhibitions. This will facilitate an identification of culture as ‘more than the arts’, which is integral to any conception of culture within a national context (Ashton & Boaden 2014: 22). Within this framework the VoA program created opportunities for touring collections from a range of localities; programs that not only build on collections in local museums, galleries and private collections, but also on a range of cultural practices.

On 29 August, 2014 the National Museum of Australia launched the Defining Moments in Australian History project. The project had used a panel of experts, including Rae Frances, Bill Gammage, John Hirst and Marilyn Lake, to compile an initial list of 100 defining moments in Australian history. The project itself was set up as a conversation, discussion and/or debate about our nation’s past. At the centre of the project are a website, social media, and community outreach processes that have endeavored to engage with the Australian public (Brown 2015). Former Prime Minister Tony Abbott happily joined this conversation when he launched the project declaring:

The arrival of the First Fleet was the defining moment in the history of this continent. Let me repeat that, it was the defining moment in the history of this continent (Dingle 2014)

This reflects not simply a natural consequence of personal opinion upon designating ‘the’ defining moments, but also Canberra’s place in the production of what nations ‘might be expected to practise in their national cities’, representing a simplified, generalised and concisely defined conception of nationality (Beer 2009: 151). The outcomes from this project, as reported by Nicholas Brown from February 2015 data, in spite of the relatively low number of hits, has seen a movement against this narrow conception of nationality.[ii] Emblematic and foundational moments have not featured amongst the alternative suggestions from the public, with locality focused activities such as the first mosque built in Maree in 1861 or the Queensland floods of 2011 amongst those voiced:

What is emerging is not so much a discussion about the ‘national story’, but more a series of voices that are cutting in at levels below the nation, seeking recognition of more localised ideas of place and identity. In itself, this is indicative of a conversation waiting to be had, of the ‘crossroads’ where the traffic reflects journeys that are underway in the minds and experience of Australians. (Brown 2015)

These contestations represent spaces the VoA program has, and continues, to operate in, melding between homogenous and heterogeneous zones. It has done this by facilitating the touring of collections and artwork both from NCIs and regional locations. Within this, it defines ‘nation’ as a multiplicity of narratives and creative practices that function as component parts of the national assemblage. One example of this is the May Lane Street Art Project, which was toured using VoA funding as MAYS by Bathurst Regional Art Gallery. The May Lane Street Art Project was established at St Peters, NSW, as a community/artist led initiative supported by Marrickville Council. St Peter’s is a semi-industrial suburb in Sydney’s inner west, located under the flight path of Sydney Airport’s third runway. In 2003 residents of May Lane gave permission to the May Lane Street Art Project for their fences, gates, garage doors and general flat surfaces facing the lane to be painted on. This created a safe, legal space for graffiti and street artists to perform their work (MAYS 2011: 7). The project has had its issues, with a number of illegal graffiti taggers, labelled vandals, who have polluted May Lane with obscenities, upsetting local residents (SMH 2010). But in the main, this project has received broad support from residents both of May Lane and the surrounding area, and has been lauded as a successful creative project that dissuades illegal graffiti. Street art is an in situ art form by nature, which is regularly impossible to remove from the place it was created. It is often battered by the elements and painted over by other artists in a continual rewrite of an artistic space. In an endeavour to bring this project to a broader audience, May Lane Street Art Project inserted blank, black, removable ‘canvas’ into unused garage door recesses to create street art that could be removed from the confines of May Lane. This formed the basis of the MAYS, when the first retrospective exhibition was held in an empty warehouse in Sydney’s inner west. A chance meeting between Bathurst Regional Art Gallery director Richard Perram and May Lane Street Art Project Director Tugi Balog in 2008 was the impetus for the exhibition which later received VoA funding.

MAYS was toured by the Bathurst Regional Art Gallery across five states, and eight locations, from 2010 to 2012. Venues included ArtSpace Mackay (QLD), Lake Macquarie Regional Gallery (NSW), and the Samstag Museum of Art (SA). It featured artworks from individual artists and artist collectives, including Mini Graff, Dlux!, Peter Burgess and Deb. MAYS is significant for the role it plays as a component of multiple assemblages, at the level of locality and nation. Graffiti has become a significant cultural construction in Australia, with numerous local councils engaging with and encouraging the production of street art in Sydney, Melbourne and most recently in Perth, where the PUBLIC street art festival has become a key event on the cultural calendar, attracting a number of international artists. This art has become a defining characteristic of urban locations ‘where it helps to construct the legitimation of transgression, yet... cannot do this without also, and at the same time, becoming a form of social capital and place branding’ (Davey, Wollon & Woodcock 2012: 39). Built within a cultural planning framework, dominated by local councils, these spaces become simplified as part of broader marketing campaigns tied to place (Stevenson 2014: 106). This ‘in situ’ aspect of street art has been acknowledged through the exhibition by ensuring that place, May Lane, St Peters, and the May Lane Project itself are cornerstones of the curatorial arrangement (French 2010: 10-11). Nonetheless, in removing these images from their sites of creation MAYS unlinks these artworks from a locality defined assemblage into a broader cultural framework that crosses aesthetic and place-based boundaries. Beyond this it also sees ‘a different form of encounter with the environment of the lane than simply stumbling upon it when walking the streets. This encounter is that of the motivated, interested, self-conscious audience member with art’ (French 2010: 8) Rather than seeking ‘recognition’ of a locality, the integration of this artwork within a broader cultural framework, as a touring exhibition that, more importantly, engages with this ‘interested’ audience, MAYS connects to cultural and locality defined networks to progress a broader conception of street art as a national production.

While working across these same cultural and locality bound networks, the exhibition Smalltown has broadened the place-based interconnections by capturing a diverse number of regional locations for delivery to urban and sub-urban settings. Smalltown was a creative collaboration between photographer Martin Mischkulnig and writer Tim Winton that explored the built form in rural and remote Australia. Curated and toured by the Historic Houses Trust (now Sydney Living Museums), it engaged these collaborators because of their strong association with regional locations, both individuals having spent extended periods living and working in small, rural communities. Their disentanglement from urban centres is reflected in both the words and images captured in the exhibition. Mischkulnig’s photographs capture a range of rural communities, focusing predominantly on place. While people populate a number of his images, it is landscapes, streetscapes, truck-stops and silos that feature in his analysis of rural Australia. And he has not restricted his selections to a single region, or state. Images include Exmouth, Western Australia; Woomera, South Australia; Barrier Highway, New South Wales; and an ethereal depiction of Bell Bay, Tasmania. This title structure (place, state), dominates throughout the exhibition, underlining place, as opposed to subject, as the key concern of the exhibition. The few exceptions are portrait images and images of road side memorial and graves. Coincidently, in her analysis of roadside memorials, Elaine Campbell posits that local sites act as analysis points within a general ‘commemorative cultural practice’ which can provide a conceptual shift that aligns with analysis of sites of collective national trauma, such as Ground Zero 9/11 (2013: 542). This concept can be expanded, to incorporate how the locally situated photographs in Smalltown operate across the public sphere, as Latour’s ‘society of assemblages’. It provides comparative sites for conception of home, conception of industry, and conception of consumption, where these sites can be examined in relation to collective comprehension of nation and national life. Winton’s text blatantly questions the cultural role of these local scenes - not only examining their structure and form, but questioning the locations' relationships to the nation and its capital cities:

Company towns evince a peculiar suburban longing. To people besieged by an enormous and overwhelming landscape, the neat kerbing and mown lawns of these communities are attempts at reassurance. They are all cul-de-sacs and shopping malls and tinkling sprinklers… Although built to look permanent, they never quite convince because they are only ever adjuncts to the mines. (Winton 2009: 20)

Tim Winton’s words form an important relationship with Mischkulnig’s images, which are displayed traditionally in the exhibition, contained within plain, wooden frames, hung equidistantly apart. Perhaps this simplicity permits the literary and visual to offer contact points that do not simply share a narrative or picture of rural Australia, but open a dialogue with the majority of the Australian population that live along the coastline and spread their suburban networks little more than 50 kilometres from these shores.

Exhibitions are constructions, curated and aesthetically designed to engage directly with audiences within a public sphere, a sphere that at times is put forward as an infinite vessel, capable of cumulating a multiplicity of perspectives, content and forms. Viewed through assemblage theory a multiplicity ‘is not a collection of "things" so much as a potentiality to move, enjoin, communicate or engage.’ (Campbell 2013: 532) From this perspective it is not simply those sites captured in the photography of Mischkulnig that are at play, but the audiences and locations with which they engage. After opening at the Historic Houses Trust’s galleries at the Museum of Sydney, Smalltown was toured across 13 locations, including the Western Australian Museum, the National Archives of Australia, Canberra, and The Arts Centre, Gold Coast. Each site presented a new engagement, one that not only created a new assemblage, which includes the intersection of exhibition, place, space, viewers, critics, but beyond this intersects with a larger assemblage of nation. As has recently been outlined by Waterton and Dittmer, not only component parts, but larger assemblages:

have relations of exteriority, meaning that they can, and often do, participate within multiple assemblages simultaneously, and therefore are not defined by their function within a single assemblage. (Waterton and Dittmer 2014: 124)

Within this framework, images of a lonely phone box at Woomera, South Australia or Woodchips, Bell Bay, Tasmania engage with audiences at major cities and urban centres. As has been outlined, assemblage theory rests upon the premise that assemblages and their components are defined by relationships of exteriority, with the consequence that ‘a component part of an assemblage may be detached from it and plugged into a different assemblage, in which its interactions are different.’ (DeLanda 2006: 10) The touring of exhibitions, unplugged from their sites of production and their insertion into new sites, creates new interactions, new assemblages, which define individual and collective relationships within this curated space:

George Main concluded his review of Smalltown with the remark:

A deeper ugliness has long operated within the hearts of modern cities, where blind and relentless exchanges of globalised commerce extract and erase the souls of distant places. (Main 2009).

It is this extraction of place that is at the heart of the exhibition Australian Minescapes. Minescapes is a photographic exhibition that illustrates mining operations in Western Australia, as captured by Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky. Burtynsky is a Canadian landscape photographer whose work focuses on large format photographs of industrialised landscapes. From high vantage points, including helicopters and light-aircraft, he captures sweeping visions of these transformed spaces. His work is represented in numerous international galleries, and is often praised for its capacity to underline the connection between sites of production and sites of consumption (Godswain 2008: 2). In 2008 Burtynsky was commissioned as part of the bi-annual FotoFreo festival run by the City of Fremantle, with financial support from BHP Billiton, to photograph select sites of Western Australia mining operations. These sites included Lake Lefroy, Kalgoorlie’s Super Pit in the eastern Goldfields and Mount Whaleback in the Pilbara. The exhibition was subsequently gifted to the Western Australian Museum by Burtynsky, with financial support from FotoFreo. The Western Australian Museum received the VoA funding to tour the exhibition to sites including Sovereign Hill Museum, Ballarat, the Australian Centre for Photography, Melbourne and the Western Australian Museum’s own site at Kalgoorlie.

In her 2013 Griffith Review essay examining the Pilbara region, Rebecca Giggs notes the careful refining of images depicting Perth’s mining industry, predominantly sponsored by the mining companies themselves (Gibbs 2013: 29). Concluding a remark on the ‘inverted’ nature of Mount Whaleback, which today is a 1.5 by 5 kilometre open-pit mine, she notes:

human imagination settles so lightly upon it – for these are places that are meant to be flown over, into and out of. To allow your mind to dwell on the meaning and history... is, in a way, politically radical (Gibbs 2013: 30)

The term ‘toxic’ or ‘industrial’ sublime has been chosen to define Burtynsky’s work, where his choice of lens and photographic negative flattens these scenes, bringing to the fore a combination of rich detail and colour to interpret the transformation of these natural landscapes (Giblett 2009: 785). Rather than a documentary style, the resultant images are stylised scenes that ‘suspend immediate judgement’ to begin a dialogue around the actors involved in these changes (Zehle 2008: 113). Images from Minescapes are, thus, not placed in this context as something ‘uniquely Australian’, but instead operate with a continuum of Burtynsky’s ‘transnational approach as his long term concern with the altered landscape’ (Ennis 2009: 79) These complex interactions, such as those between artist, locality, audience, and society, is at the heart of assemblage theory; it is also that aspect which is the most difficult to define due to the ‘bewildering array of participants [that] is simultaneously at work in them and which are dislocating their neat boundaries’ (Latour 2005: 202). These neat boundaries continuously attempt to redefine themselves, in progressive attempts to stabilise assemblages. For Minescapes it is how these images of open-cut mines, and the resultant changes to Australia’s interior, are traversed into urban sites to redefine a conception of Australia, and imbed and normalise within a broader Australian culture, that is at play.

Assemblage theory presents a significant pedagogical shift, with consequences for the exploration of locality and nation, and the complex relationships through which they intersect. If one were to examine touring exhibitions within the conventional approach to cultural studies, what Latour defines as the ‘sociology of the social’, then these exhibitions and their content would be analysed for their capacity to integrate, or contest, an existing social ‘whole’ that is behind everything else (Latour 2005: 8). Assemblages, while operating within a network of connections, and within large assemblages, nonetheless, all have relative levels of homogeneity or stability. This conceptualisation rests most heavily in processes of the territorialisation and deterritorialisation of the social construct of nation and national culture. DeLanda has illustrated this de/territorialisation as a spectrum, defined as the process through which individual ‘components become involved and that either stabilise the identity of an assemblage, by increasing its degree of internal homogeneity… or destabilise it’ (DeLanda 2006: 12).

The VoA program operates as a stabilising force for national culture, in spite of the complications it presents in the conceptualisation of nation through the presentation of a heterogeneous suite of ‘visions’. As stand-alone sites, constructs representing a diversity of perspective, these exhibitions could be seen as a deterritorialising force, one that decreases the degree of homogeneity in the ideal of nation. Both Mays and Australian Minescapes are focused on defined localities, which operate within spheres of segregation and congregation that are defined by their physical structures and the ‘circulation of matter and energy’ that subsequently define a sense of space and community (DeLanda, 94). Nonetheless, these exhibitions also operate in a public sphere, one that is not only defined by their relationship to the sites of touring, but also the funding agency that enables this touring. As has been identified by Kay Anderson in her analysis of C3West, the Government funding body is a further active component in the assemblage. As described by Anderson:

Funding generates a further interface between funder and funded. Along with the provision of money comes agreement to deliver certain outcomes, which in turn entails timescales, protocols and reporting requirements. Funding anchors the follow of resources and administrative actions within a framework of bureaucratic accountability. (2009: 147)

One of the definitive requirements of the VoA program is that an exhibition must tour a minimum of 3 interstate locations; that is locations outside the state in which the touring institution is based (Australia Council 2015). Within this context, these exhibitions are identified as having value to the broader Australian community, and are recognised as contributing to a rarefied Australian culture that is influenced by a spectrum of relationships. Latour identifies this process and movement as times when the social can be detected; moments where we can trace ‘associations through many non-social entities which… if pursued laterally… may end up in a shared vision of a common world’ (Latour 2005: 247). In this way, VoA can be seen to nominate these exhibitions into a broader framework of Australian culture, with outcomes tied to the way that this nation is defined in relation to, and interaction across, national, regional, urban and suburban components. This concept blends with Latour’s ‘society of assemblages’, where each individual assemblage’s integrity is determined by its ‘safer connections’ with other assemblages inside a network of intersections.

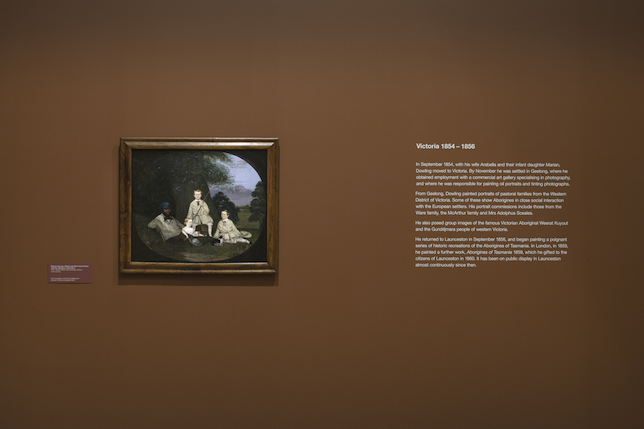

This has consequence for VoA’s operation within a national culture dominated by NCIs and their setting within the national capital, Canberra, with consequences for the construction and distribution of culture within and across communities. To understand this further it is necessary to analyse how exhibitions toured by national collecting institutions interact with the localities they tour. Robert Dowling: Tasmanian son of empire was toured by the National Gallery of Australia using funding from both VoA and NCITO. From the outset it had been forecast as a touring exhibition, with the exhibition opening in the focus artist’s home town Launceston, at the Queen Victoria Museum & Art Gallery (QVM&AG), before proceeding to Geelong Art Gallery, a place that Dowling practised in the 1850s, before concluding at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra (Jones 2010: 12). Eighteen of the 67 works featured in the exhibition are from the QVM&AG, so it is fitting that this institution opened the exhibition to the public for the first time. Chris Beer has made the argument that NCIs are defined by their relationship to Canberra, as the nation’s capital city (Beer 2009: 151). He posits that they are performative spaces that are ‘orientated towards the production of the imagination and practice of the Australian nation in the future’, which are designated as both arbiters and creators of national space (Beer 2009: 151). By opening the tour at the QVM&AG and concluding at the National Gallery of Australia, Robert Dowling has been removed from a future focused orientation at the heart of Canberra’s cultural production. This is relevant in the touring exhibition and accompanying publication that deliberately focus upon the localities where Dowling practised early in his career, at Launceston and Geelong, before moving on to his career in Europe and final years at Australia’s future (temporary) capital of Melbourne. In doing so, this exhibition has inverted the traditional exhibition schedule for NCI’s touring exhibitions. In doing so it redefines the relationship between capital and locality, questioning the concept of a set, capital oriented, national culture.

Robert Dowling: Tasmanian son of Empire exhibition, National Gallery of Australia, 2010. Image courtesy National Gallery of Australia.

Within a ‘society of assemblages’, with the consequent fracturing of a metropole and periphery, those exhibitions that are developed in Canberra and toured nationally, can be approached as a more fluid and malleable cultural production than previously considered. They may also be examined as not only a medium for transporting conceptions of nation between ‘micro places’, but part of the redefinition of these places. There were a number of exhibitions in VoA Round 32 that followed a traditional touring exhibition schedule, with Exposed: The story of swimwear and Shell-shocked: Australian after Armistice both exhibited at their touring NCI, respectively the Australian National Maritime Museum and the National Archives of Australia, before being sent to a variety of interstate locations. However, the inversed nature of touring Robert Dowling underlines the capacity of the VoA program to ‘flatten the social’, bringing locally defined material to the fore, and highlighting the interactions to and from these locations while still maintaining those ‘safer connections’ within (and to) Canberra. As such, the touring of regionally developed exhibitions into Canberra has consequences for the stabilisation of these assemblages and their integration into a broader national culture. The National Archives of Australia’s hosting of Smalltown, connecting this exhibition to the internal and external relationships inherent in Canberra, provides a case in point for this analysis.

The Visions of Australia program has for more than 20 years played a significant role in making Australia’s culture accessible to a range of communities, across numerous states, in both urban and rural locations. In doing this, it has increased the visibility of regionally and locally developed exhibitions, as well as touring the significant collections of the National Collecting Institutions based in Canberra. The introduction of the National Collecting Institutions Touring and Outreach program, and its subsequent extension, provides fertile ground for examining further the role of Canberra and these institutions in defining a national culture. As has been illustrated, this same national culture is a more complex and heterogeneous amalgamation that defies any conception of a dominant metropolitan centre. Within an assemblage framework, rather than competing against a dominant, entrenched, national culture, these exhibitions influence and define the broader national culture through their interactions with a variety of populations, bolstered by the validity given to these programs through a nationally funded grant program. To appropriately analyse this relationship it is necessary to flatten our conception of nation, from one based upon capitals, a central narrative and/or prominent individuals to one that acknowledges a complicated, heterogeneous and social national culture defined by the intersection of localities. In doing this it is ventured to move beyond confined and detailed analysis of individual exhibitions, which, while valid, deny or cloud the capacity of defined assemblages to be redefined by relationships of exteriority and, from this, their capacity to define a larger national culture through their component capacities. The VoA program, with its multiplicity of perspectives, audiences and touring institutions, underlines a heterogeneous national culture, one that is fluid and continually redefined.

[i] National Collecting Institutions not mentioned by name in the article, but still relevant for this discussion, are National Portrait Gallery, Bundanoon Trust, Museum of Australian Democracy and the National Film and Sound Archive.

[ii] The Defining Moments in Australian History webpages had received 22,500 hits as of the 18 February 2015.

Australia Council for the Arts, Visions of Australia webpage, at http://www.australiacouncil.gov.au/funding/new-grants-model/visions-of-australia-regional-exhibition-touring-fund/ (accessed 20 April 2015)

Anderson, K 2011 ‘Theorising Arts-Led Collaboration as Assemblage’, in The Art of Engagement: Culture Collaboration, Innovation, Crawley WA: University of Western Australia Press, 139-149

Ashton, P and Boaden, S 2015 ‘Mainstreaming Culture: Integrating the cultural dimension into Local Government’ in P Ashton, C Gibson and R Gibson (eds) By-roads and hidden treasures: mapping cultural assets in regional Australia, Crawley: University of Western Australia Publishing, 19-36

Balog, T 2010 MAYS: The May Lane Street Art Project Guide, Bathurst NSW: Bathurst Regional Art Gallery

van Barneveld, K 2009 ‘Australia’s Cultural Institutions and the Efficiency Dividend: Not a pretty picture’, Public Space: The Journal of Law and Social Justice 3: 5, 1-28

Beer, C 2006 The Production of Canberra and Its National Cultural Institutions: Imagination and Practice of National Capital Space, National Leadership and Transnational and National Museum Practice, and Commonwealth Managerial Space, Refereed paper presented to the Australasian Political Studies Association conference, University of Newcastle, 25-27 Sept 2006

Beer, C 2009 The national capital city, portraiture, and recognition in the Australian mythscape: The development of Canberra’s National Portrait Gallery. National Identities, 11: 2, 149-163

Bennett, T and Healy, C 2013 ‘Introduction: Assembling Culture’ in T Bennett and C Healy (eds) Assembling Culture, Abington: Routledge, 1-8

Brown, N 2015 ‘History on demand: Defining moments in Australian history’, Recollections: Journal of the National Museum of Australia, 10: 1, athttp://recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/volume_10_number_1/commentary/history_on_demand (accessed 27 October 2015)

Campbell, E 2013 ‘Public sphere as assemblage: the cultural politics of roadside memorialisation’, The British Journal of Sociology, 64: 3, 526-527

Davey, K, Wollan, S, and Woodcock, I 2012 ‘Placing Graffiti: Creating and Contesting Character in Inner-city Melbourne’, Journal of Urban Design, 1: February 2012, 21-41

DeLanda, M 2006 A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity, London: Continuum

Dingle, S 2014 Tony Abbott names white settlement as Australia’s ‘defining moment’, remark draws Indigenous ire. 31 August 2014, at http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-08-30/pm-comment-on-defining-moment-angers-indigenous-groups/5707926 (accessed 27 October 2015)

Ennis, H 2009 ‘Edward Burtynsky’s Minescapes: An Australian Perspective’, in R Coffey (ed) Australian Minescapes/Edward Burtynsky, Welshpool: Western Australian Museum

French, B 2010 ‘Painting in Situ: Wooden panels and cracked brick walls’, in T Balog (ed) MAYS: The May Lane Street Art Project Guide, Bathurst: Bathurst Regional Art Gallery, 7-11

Giggs, R 2013 ‘Open ground: Trespassing on the mining boom’, Griffith Review, 47, South Brisbane: Griffith University in conjunction with Scribe Publications

Godswain, P 2008 ‘BOOM: Mining, photography, landscape and the City’, The New Critic, 8: September 2008, at http://www.ias.uwa.edu.au/new-critic (accessed 15 April 2015)

Hillias, J 2011 ‘Encountering Deleuze in Another Place’, European Planning Studies, 15: 5, 861-885.

Jones, J 2010 Robert Dowling: Tasmanian son of empire, Canberra: National Gallery of Australia.

Latour, B (2005) Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Main, G 2012 ‘Exhibition review: Smalltown’, Recollections: Journal of the National Museum of Australia, 7: 1, at http://recollections.nma.gov.au/issues/volume_7_number_1/exhibition_review/smalltown (accessed 2 May 2015)

Ministry for the Arts, Visions of Australia successful grant recipients webpage, at http://arts.gov.au/regional/visions-australia/recipients (accessed 20 April 2015)

Ministry for the Arts, National Collecting Institutions Touring and Outreach webpage, at http://arts.gov.au/collections/ncito (accessed 20 April 2015)

Sydney Morning Herald. “Graffiti gallery filth earns spray from residents. 19 October 2010, at http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/art-and-design/graffiti-gallery-filth-earns-spray-from-residents-20101018-16qx9.html (accessed 10 May 2015)

Stevenson, D 2014 ‘Locating the Local: Culture, Place and the Citizen’ in P Ashton, C Gibson and R Gibson (eds) By-roads and hidden treasures: mapping cultural assets in regional Australia, Crawley: University of Western Australia Publishing, 19-36

Robert Trudgeon and Tim Sullivan interviewed by Margaret Burin, 4 March 2010, 107.9 ABC Ballarat, at http://www.abc.net.au/local/audio/2010/03/04/2836841.htm (accessed 5 May 2015)

Waterton, E and Dittmer, J 2014 ‘The museum as assemblage: bringing forth affect at the Australian War Memorial’, Museum Management and Curatorship, 29: 2, 122-139.

Witcomb, A 2009 ‘Migration, social cohesion and cultural diversity: Can museums move beyond pluralism?’, Humanities Research, XV: 2, 49-66

Winton, T and Mischkulnig, M 2009 Smalltown, Camberwell, Victoria: Penguin

Zehle, S 2008 ‘Dispatches from the Depletion Zone: Edward Burtynsky and the Documentary Sublime’, Media International Australia, Incorporating Culture & Policy, 127: 3, 109-115